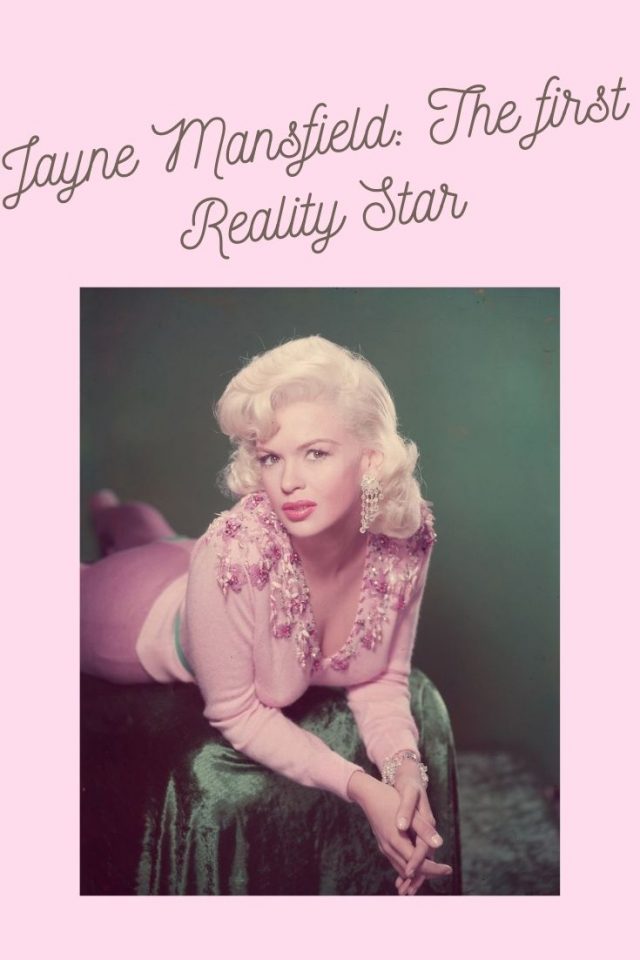

ayne Mansfield: The First Reality Star

For broadcast journalist Elaine Stevens, now 68, it feels like it happened only yesterday. It happened exactly 50 years ago today.

Stevens answered the door to her parents’ Gulfport, Mississippi, home. Her fiance, Ronnie Harrison, stood before her. Describing him today, Stevens still sounds 18: “He looked like Matthew Modine or Ralph Fiennes.” The couple was planning to elope three days later; Stevens was carrying their child. “The last thing he said to me was, ‘Will you always love me?’ And I said, ‘Of course I will. I’ll always love you.'”

That was the last time they ever saw each other.

Two hours later and 500 miles away, another woman, Vera Peers, awoke in a panic. Her daughter, Jayne Mansfield, had appeared to her in a dream. Standing atop a large, white stairwell, she was screaming, “Mama, I have a story to tell you. You have many steps to go. I’m at the top now, but I’ll be waiting for you.”

Vera awoke to the shriek of a police car’s wheels at her front door.

Jayne Mansfield, 34, movie star, mother and mother of invention, was gone, dead from a car crash on Highway 90 in Slidell, Louisiana, en route to New Orleans. Also killed with her were her attorney, Sam Brody, and their driver, Stevens’ fiance, Ronnie Harrison. All three children in the car — Mickey Jr., Zoltan and Mariska Hargitay — survived.

Jayne Mansfield was nobody’s fool. The world’s smartest dumb blonde appeared in 27 films (only a handful of them memorable). But her bid for immortality lives on — not just in the lives of her children, but in a thriving, “famous-for-being-famous” culture she helped to create.

Before stars could reach millions of followers in 140 characters and 60 seconds or less, Twitter’s equivalent name was Hedda Hopper. Facebook, too, had one: Louella Parsons. These, along with a dozen other syndicated Hollywood power brokers, formed a mainline to the heart of the American people. And Jayne was their pied piper, adept as any modern-day social media maven at keeping herself in the public eye.

If it weren’t for Mansfield then, there would likely be no Kardashians today.

Mansfield’s leverage of the press was never more potent than in 1957 when she seemed poised to take over the world.

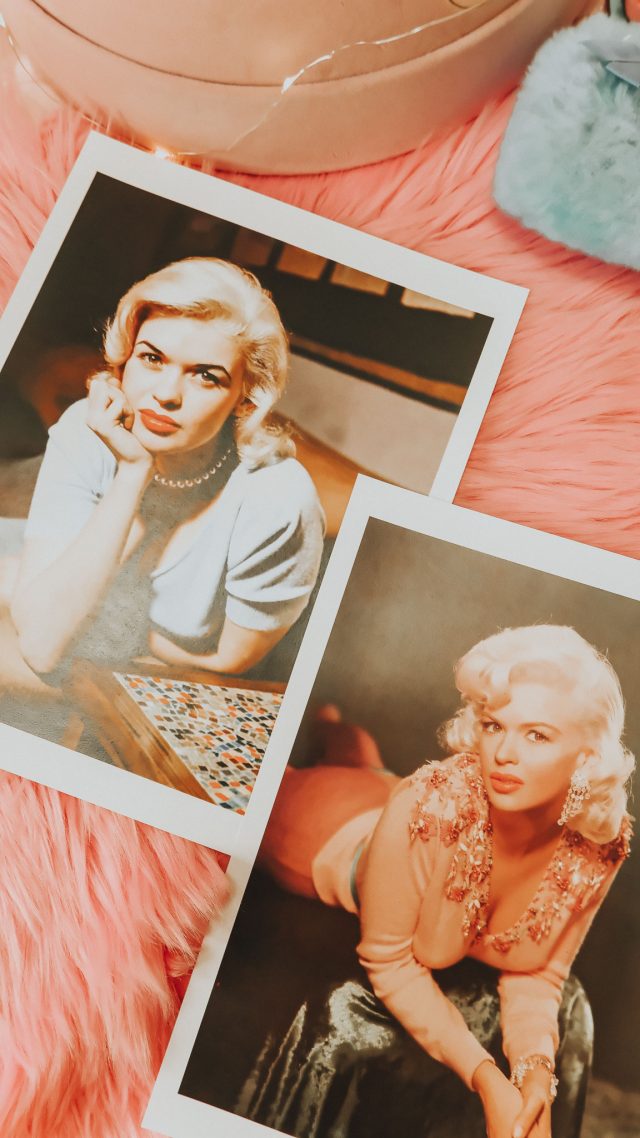

Borrowing the test-driven public persona of Marilyn Monroe, Mansfield beat out Monroe herself in popularity polls. She had four significant features under her belt, and Twentieth Century Fox estimated her worth at $40 million ($350 million today). Mansfield’s name was “magic at the box office,” Parsons wrote.

On tour with Bob Hope, Mansfield brought 100,000 servicemen to their feet (co-star Neile Adams remembers her “in a bikini in Alaska in -20-degree weather”). Mansfield’s impact on men was likened to Elvis Presley’s on women, leaving riots in her wake. She had, as columnist Walter Winchell put it, “the world in the palm of her little pink hand.”

So why is Jayne Mansfield barely remembered today?

The answer may lie in a single item that appeared in Hopper’s column at the turn of 1957: “Jayne Mansfield is pushing ahead too rapidly.”

She was pushing 60 years ahead of her time.

Less than three years before her meteoric rise, Mansfield, 20, left Texas for Hollywood with husband, Paul, and their first child, baby Jayne Marie, in tow.

Vera Jayne Palmer was a violin and piano prodigy; her instructors felt she would someday conquer Carnegie Hall. She spoke five languages and boasted an I.Q. of 163. At one of three colleges she would attend, Jayne (she dropped the “Vera”) studied chemistry, abnormal psychology and drama — a seeming recipe for success in Hollywood.

In Dallas, where she lived for a time with her husband, Jayne studied with Baruch Lumet — celebrated Yiddish Theatre actor and director Sidney Lumet — who directed her in a “perfect” performance, Death of a Salesman. The Seagull was one of her favourites, and she longed to play Blanche DuBois.

Texas journalist John Bustin, who had known Mansfield since her theatrical debut in Austin Civic Theatre’s Ten Nights in a Bar-room in 1951, wrote of her potential in 1954: “She might prove bigger than, say, Jane Russell in a couple of years.” He was right — except it was only a matter of months before Mansfield put that I.Q. to use.

In January 1955, Mansfield scored a plus-one to a press junket for Howard Hughes’ Underwater starring Jane Russell. Outfitted in a skintight red lamé swimsuit, Mansfield dove into a pool and, according to journalists, “had the genius to permit her bathing suit to split open.”

Overnight, Mansfield’s image was plastered across America as “Marilyn Monroe, king-sized.” In a Person to Person interview broadcast live before 20 million, Edward R. Murrow inquired about the wardrobe malfunction — to which Jayne replied innocently, “I don’t remember the incident.”

“Ever since Underwater, the press just adopted her,” says Ray Strait, 93, Mansfield’s former press secretary and biographer. It was Mansfield who hacked the system: Tapping into a sweet spot of marketing known as “optimal newness,” she presented a brand that was an ideal blend of both originality and derivation — a replica of Monroe who went just a bit further.

Warner Bros. signed her briefly, marketing her as their “threat to Marilyn Monroe.” She tested for Rebel Without A Cause (Natalie Wood got the part), booked small roles (including an echo of Monroe’s breakout role in Asphalt Jungle in a film called Illegal) and posed for Playboy.

Paul Mansfield, recognizing that he would always be the second choice to his wife’s career, filed for divorce and custody of their daughter. Jayne claimed Paul was jealous of her Chihuahua — and won. It turned out that flying solo worked to her advantage.

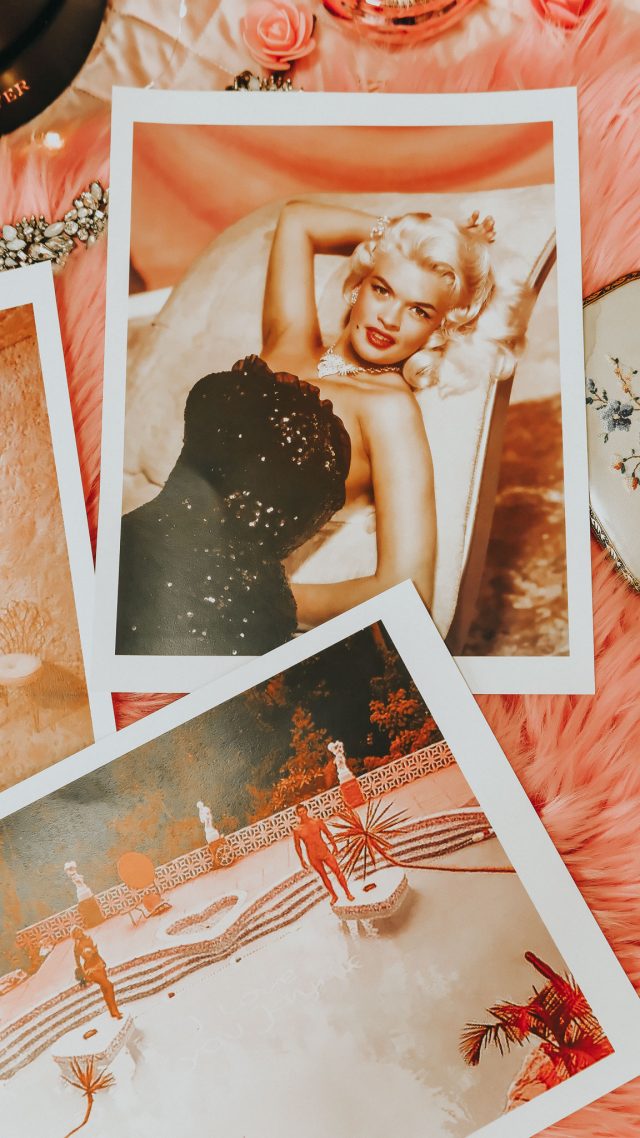

While men had always fancied Mansfield, women now sympathized with her. She became, ostensibly, the first sex symbol to wipe Freud’s “Madonna-whore complex” from the psyche of millions of American men. After all, who could fault a single mother who posed nude for Playboy “to pay for milk and food for the baby”?

Mansfield kept her last name but lost her Warner’s contract. It wasn’t long, though, before lightning struck again.

Headlines blared “Marilyn Monroe Is Due for Surprise” when Mansfield conquered Broadway in 1955’s Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? Aping Monroe, she snagged a Theatre World Award and raves for her performance as a blonde movie queen. Her co-star Orson Bean, 88, recalls fondly: “It became a hit because of Mansfield and all the publicity. She is the only performer who was on the cover of Life magazine twice in one year!”

Indeed, every day became Underwater for Jayne. In addition to managing motherhood, a melange of pets and a full-time show schedule, she orchestrated three to five personal appearances, photoshoots, interviews and endorsements per day. “I’m serving a kind of internship here,” she said. She was building an empire.

With Monroe sitting strike at Fox (she sought greater creative and financial control over her work), it wasn’t long before the studio sent scouts to size up Mansfield. Fox gave her a powerful launch, producing Mansfield’s most significant body of work — The Girl Can’t Help It, the film version of Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? and The Wayward Bus — in the first year of her contract. With strong reviews and respectable box office sales, Mansfield earned a Golden Globe Award, fulfilling Parsons’ prophecy that, in 1956, it would be “Mansfield to win, Loren to place, Monroe to show.”

Fox had signed Mansfield as a bargaining chip in the face of Monroe’s insubordination. But what the studio hadn’t counted on was that their new star would display defiance all her own.

Like other sex symbols of her era, Mansfield was encouraged to date within the studio’s stable and not have children, a mandate to which she agreed — initially: “Too many Hollywood stars are getting married too fast,” she quipped in 1956. “I’ll devote myself to work during this seven-year contract. After that, I can have four kids. This town was built on glamour, not babies.”

A little over a year later, however, she married former Mr. Universe Mickey Hargitay. Although her proclaimed wish for “a quiet, dignified” wedding, 90 percent of her guests were newspapermen — and an estimated 8,000 spectators turned up after she revealed the locale, the glass-panelled Wayfarers Chapel in Rancho Palos Verdes, in the papers.

In short order, the second of Mansfield’s five children were on the way. Her embrace of motherhood set a precedent for other leading ladies, becoming an expression of her femininity rather than a deterrent. One wonders if Mansfield became famous for underwriting her love of children (she wanted “500,” she told reporters) or if, in an early bid for feminism, she had children to prove to the world that women could have it all. Either way, pregnancy did not sit well with the Fox image factory, which cost Mansfield roles.

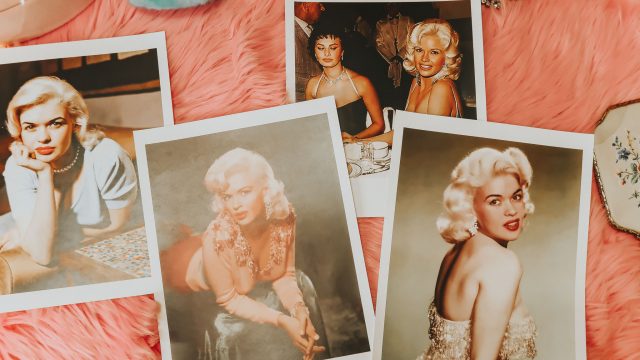

As Monroe came back into the fold at Fox, Mansfield bucked the studio’s publicity machine and engineered stunts to gain traction. One event in particular branded her in public memory.

“The party was in full swing when Jayne arrived,” recalls Mitzi Gaynor, “gorgeous and at her most platinum. It was one of those oh-so-showbiz moments when the whole room seems to stop for an instant. She sensed it, seized the opportunity, and the rest is history.”

The soiree at Romanoff’s, celebrating Sophia Loren’s American debut, became something of a coming-out party for Mansfield’s decolletage instead. While Mansfield denied any premeditation — or even awareness — of the spillage, friend and fellow contract player Robert Wagner remembers differently. He laughs when recalling how he spotted the “sweet and “marvellous star, whom he often accompanied to premieres, from his car at a red light en route to the party. “I see her in her car, and she’s putting rouge on her nipples!”

The girl couldn’t help it.

Fox was beside itself. Stars were meant to be unattainable; a movie ticket was the price of access. However, “would open a cracker box if she thought it would get the press there,” recalls Strait. “She had to have that spotlight all the time.”

The consequences of this pursuit began to reveal themselves in the columns of those who’d helped launch her career: “She has been far too accessible to every lensman, scribe and high school reporter,” barked columnist Dorothy Kilgallen.

If the studio couldn’t shake her of the habit, it could punish her — and did. At $200,000 per picture, Fox loaned Mansfield out to studios overseas while retaining her services at $1,250 per week. The quality of her films diminished, as did her cachet.

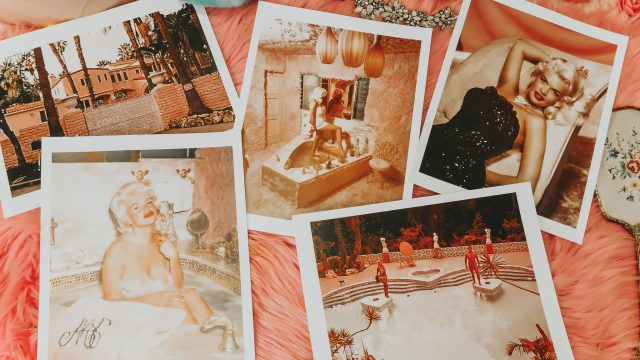

Fond of telling reporters, “If you’re going to be a movie star, you should live like one,” Mansfield fulfilled the fantasy by purchasing a Sunset Boulevard palazzo in 1958 and re-christening it “The Pink Palace.” She preferred purple, but since Columbia chief Harry Cohn had already dubbed Kim Novak “the lavender blonde,” Mansfield exhibited her branding genius — again. “Now I had a gimmick,” she declared, replete with matching pink car, furs and poodle.

With the Palace came mounting expenses, and Jayne’s business acumen kicked into high(er) gear.

As one of Las Vegas’s first — and highest-paid — female headliners, she earned $200,000 for ten weeks of work: Fox’s loan-out fee for an entire motion picture. She built an adjunct career leveraging her notoriety in exchange for cash, food and furnishings for her family and menagerie of pets — to the tune of $10,000 per ribbon cutting. A 1961 Associated Press headline trumpeted her ingenuity: “She has found a way to capitalize on fame which may create an entirely new kind of star. There’s not much to the part, but the pay is spectacular.”

“To merchandise her popularity outside of films, she did exactly what she should’ve done,” notes Derek Thompson, author of the best-selling Hit Makers: The Science of Popularity in an Age of Distraction. “As tastes changed at the gatekeeper level, she went directly to the people. She was innovative because she had to be.” For Mansfield, the motivation was simple: “I turned $2,000,000 worth of publicity into $300,000 cold cash. That was my objective. It still is.”

Once again, she hacked the system.

And then, in 1962, the world changed. Marilyn Monroe was dead — and with her passing, the era of the blonde bombshell was over.

The day of Monroe’s death, a small item ran in the papers indicating that Mansfield had been dropped from Fox. The perfect storm that had brought her to the studio had now taken her from it.

The day after Monroe’s passing, it was reported that Mansfield was separating from Mickey Hargitay, whom many considered to be her Rock of Gibraltar. She told reporters before telling him.

If Mansfield had hacked the system in the ’50s, she would crash it in the ’60s. She had spent years “out-Monroe-ing Monroe.” Now she was determined to out-Mansfield Mansfield.

After telling columnist Earl Wilson that “nudity just doesn’t mix well with motherhood,” she starred in Promises, Promises — breaking ground as the first major star to appear in a nude scene onscreen. While Mansfield’s appearance in the film kicked open doors that would be entered by countless actresses after her, it also ruptured a social contract she had worked hard to maintain — that of “accidental exposure.”

Again, there was a method to her madness: Contradiction, by design or caprice, had been her call-in-trade since the dawn of her career. Mansfield was typical to tell reporters “I’m through with cheesecake” before crossing a busy intersection in a leopard-print bikini, causing a three-car pileup. “I’m done with publicity,” she alerted the press at a Catholic funeral service held for her pet Chihuahua, Galina.

There was likely a genuine desire behind all of these statements — but there was also an intrinsic understanding that when audiences grow habituated to a product, that product grows obsolete. The solution, then, was dishabituation — the deliberate disturbance of audience expectation. Madonna may have mastered it, but Mansfield started it.

A funny thing happened after Promises, Promises. Jayne had shown audiences more, and now they expected more — at a lower price. While she continued making films, touring with a nightclub act and even starring in plays, public interest shifted almost entirely from the roles she played to the person she had become. Referring to herself as “a goldfish,” Jayne’s medium, at last, became her message.

“She can sell newspapers and magazines, attract millions of television viewers and draw crowds everywhere she goes,” wrote a Canadian journalist, “but at the movies, she’s a big bust … It could be that the public got so much of Jayne Mansfield for free that paying for the same privilege was too much.” Another critic asked, “She acts? Who cares?”

If there was a note of tragedy to Mansfield’s life, this was it.

Mansfield told Parsons in 1956, “I want to be a great actress.” But shortly afterward, she said rival columnist Sheila Graham, “The real stars are not good actors or actresses. They’re personalities.” The conflict illustrated by these statements was one with which Mansfield wrestled for the entirety of her career.

On a whistle-stop promotional tour for the film adaptation of Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? Jayne began telling journalists that, more than anything, she wanted to play Hamlet. They thought she was joking.

After meeting Mansfield in 1957, Love Boat and Mary Tyler Moore Show star Gavin MacLeod, 86, recalls a fortuitous encounter with Ben Bard, director of new talent development at Fox. Bard — who had moulded stars as diverse as Alan Ladd, Mickey Rooney and Olivia de Havilland — told MacLeod in no uncertain terms, “Jayne Mansfield was the best Hamlet I ever saw.”

Mansfield once said of herself and television, “we were meant for each other.”

From her earliest appearances, co-stars, from Carol Burnett to Jerry Lewis to Jamie Farr to Regis Philbin, remember her with great fondness, and she remained a prolific presence on talk shows in later years. Hairdresser-cum-song stylist Monti Rock III, who appeared with Mansfield on a memorable episode of The Merv Griffin Show, remembers the “extraordinary, incredible lady” who took him under her wing: “She taught me about the importance of the press,” he recalls. “It took someone like Jayne to help me understand who I was: I was famous for being famous.”

P. David Ebersole, who, with Todd Hughes, co-directed the upcoming documentary, Mansfield 66/67, points out, “She was the first star to create the idea that the public needed to know who you are — not just the public persona, but behind closed doors.”

Toward that end, in 1965, Mansfield produced and starred in a pilot playing an actress who wants to do Shakespeare — but settles for playing Jayne Mansfield instead. Part sitcom, part proto-reality show, The Jayne Mansfield Show seemed a natural fit for the actress who had already surrendered a good portion of her private life to public consumption. Thirty years ahead of its time, it was quietly shelved by NBC.

“By today’s standards, her act was extremely tame,” recalls Stevens, whose fiance died with Mansfield in that fatal car crash. “But at that time, she was like the original Lady Gaga. She had a brand, and it was called ‘Jayne Mansfield.’ And, like most women of her day, she did what she had to do to keep her family fed.”

Stevens, the author of the forthcoming memoir, Mermaid in the Window, still finds the events of 1967 “extremely painful.” After the crash, she was forced to give up her child for adoption. It would be more than 30 years before Stevens would see her daughter again. When the two reunited in 1999, “It was just remarkable seeing part of Ronnie walk the earth again.”

Stevens feels that reporters at the accident site were “a precursor to the paparazzi fascination with [Princess] Diana,” heralding a deeper dive into an era of no-holds-barred journalism in which Mansfield, regrettably, had a stake.

Despite her explosive popularity in 1957, Mansfield’s film work never did engage the public imagination in how Marilyn Monroe’s had (few ever would). What Fox could orchestrate visually, they couldn’t manufacture chemically. While the reasons for this are ineffable, one cannot help but observe that Monroe’s allure presented itself as an invitation, while Jayne’s was more of a mandate. While Marilyn was unattainable, Jayne was entirely available. There was little for audiences to chase, so Mansfield chased them instead.

A 1967 Los Angeles Times elegy concluded that Mansfield’s ingenuity led her to confuse “publicity and notoriety, stardom and celebrity.” Then-editor of Daily Variety, Joe Schoenfeld, added that Jayne had “won what our culture instructed her to achieve. And don’t sell her achievement short.” Had she survived, that achievement might have led to a cinematic re-discovery by the likes of Fellini, Almodovar or John Waters, according to documentarian Todd Hughes. At the very least, it would have yielded an online following rivalling that of any social media superstar.

In 1964, she engaged in a publicity campaign called Jayne Mansfield For President. Who knows? In today’s world, she might have won.