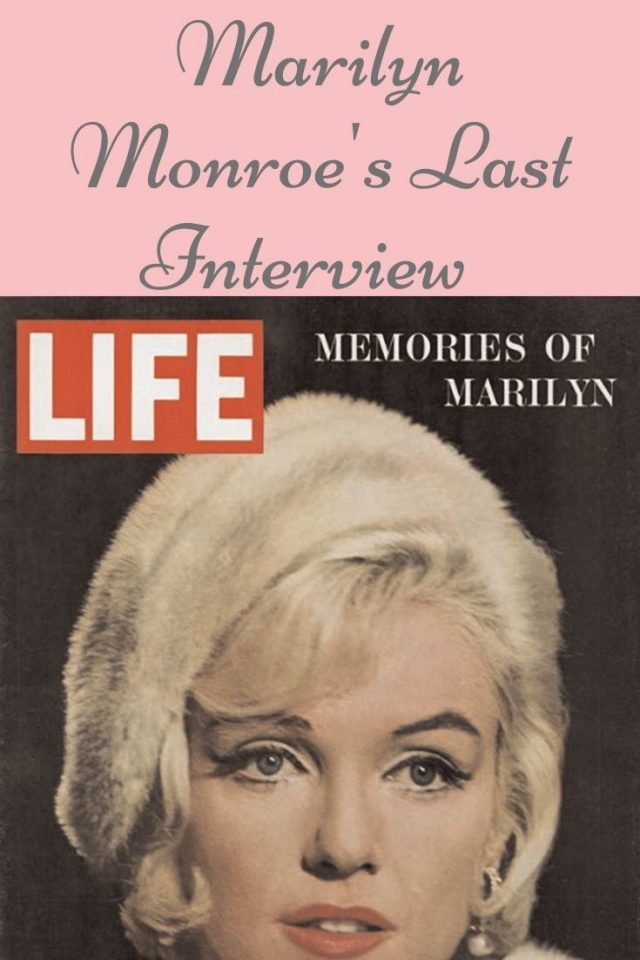

Hello lovelies, in today’s video I will reading Marilyn Monroe’s last interview from Life Magazine called Last Talk with a Lonely Girl.

When you’re famous you run into human nature in a raw kind of way’

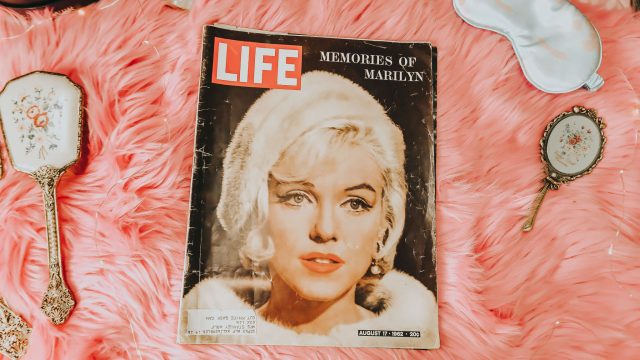

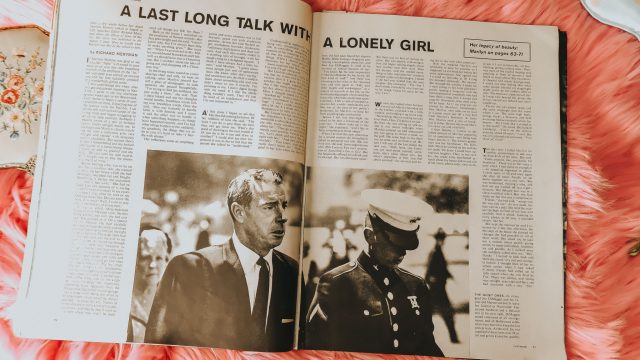

This is an edited version of Last Talk With a Lonely Girl: Marilyn Monroe by Richard Meryman, first published in Life magazine, August 17 1962

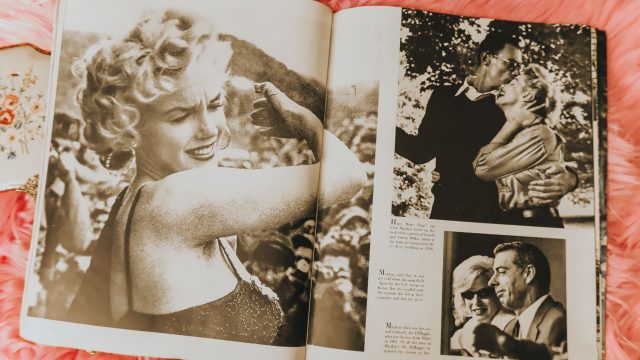

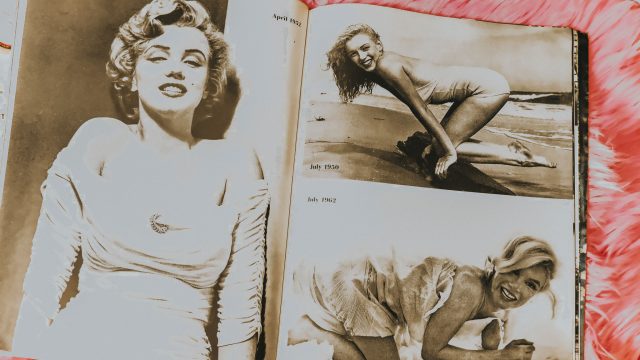

Ever since she was fired from Something’s Got to Give, Marilyn Monroe has kept an almost disdainful silence. As far as her troubles with 20th Century Fox were concerned, she simply said she had been too sick to work – not wilfully tardy and truant as the producer charged. While 20th Century Fox and her lawyers were negotiating for her to resume work on the movie, Marilyn was thinking about broader aspects of her career – about the rewards and burdens of fame bestowed on her by fans who paid $200 million to see her films, about drives that impel her, and about echoes in her present life of her childhood in foster homes. She thought about these out loud in a rare and candid series of conversations with Life associate editor Richard Meryman. As a camera caught the warmth and gusto of her personality, Marilyn’s words revealed her own private view of Marilyn Monroe …

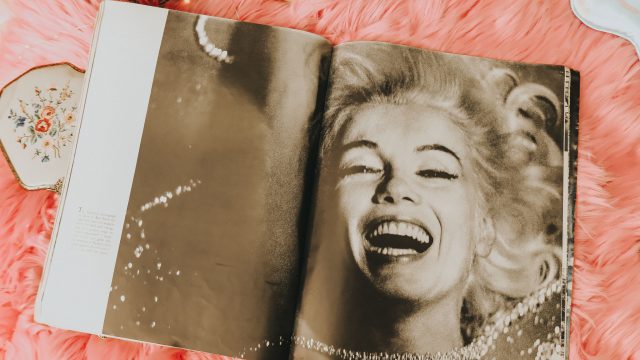

Sometimes wearing a scarf and a polo coat and no makeup and with a certain attitude of walking, I go shopping or just look at people living. But then you know, there will be a few teenagers who are kind of sharp and they’ll say, “Hey, just a minute. You know who I think that is?” And they’ll start tailing me. And I don’t mind. I realise some people want to see if you’re real. The teenagers, the little kids, their faces light up. They say, “Gee,” and they can’t wait to tell their friends. And old people come up and say, “Wait till I tell my wife.” You’ve changed their whole day. In the morning, the garbage men that go by 57th Street when I come out the door say, “Marilyn, hi! How do you feel this morning?” To me, it’s an honour, and I love them for it. The working men, I’ll go by and they’ll whistle. At first they whistle because they think, oh, it’s a girl. She’s got blond hair and she’s not out of shape, and then they say, “Gosh, it’s Marilyn Monroe!” And that has its … you know, those are times it’s nice. People knowing who you are and all of that, and feeling that you’ve meant something to them.

I don’t know quite why, but somehow I feel they know that I mean what I do, both when I’m acting on the screen or when if I see them in person and greet them. That I really always do mean hello, and how are you? In their fantasies they feel “Gee, it can happen to me!” But when you’re famous you kind of run into human nature in a raw kind of way. It stirs up envy, fame does. People you run into feel that, well, who is she who does she think she is, Marilyn Monroe? They feel fame gives them some kind of privilege to walk up to you and say anything to you, you know, of any kind of nature and it won’t hurt your feelings. Like it’s happening to your clothing. One time here I am looking for a home to buy and I stopped at this place. A man came out and was very pleasant and cheerful, and said, “Oh, just a moment, I want my wife to meet you.” Well, she came out and said, “Will you please get off the premises?” You’re always running into people’s unconscious.

Let’s take some actors or directors. Usually they don’t say it to me, they say it to the newspapers because that’s a bigger play. You know, if they’re only insulting me to my face that doesn’t make a big enough play because all I have to say is, “See you around, like never.” But if it’s in the newspapers, it’s coast-to-coast and all around the world. I don’t understand why people aren’t a little more generous with each other. I don’t like to say this, but I’m afraid there is a lot of envy in this business. The only thing I can do is stop and think, “I’m all right but I’m not so sure about them!” For instance, you’ve read there was some actor that once said that kissing me was like kissing Hitler. Well, I think that’s his problem. If I have to do intimate love scenes with somebody who really has these kinds of feelings toward me, then my fantasy can come into play. In other words, out with him, in with my fantasy. He was never there.

It’s nice to be included in people’s fantasies but you also like to be accepted for your own sake. I don’t look at myself as a commodity, but I’m sure a lot of people have. Including, well, one corporation in particular, which shall be nameless. If I’m sounding picked on or something, I think I am. I’ll think I have a few wonderful friends and all of a sudden, ooh, here it comes. They do a lot of things. They talk about you to the press, to their friends, tell stories, and you know, it’s disappointing. These are the ones you aren’t interested in seeing every day of your life.

Of course, it does depend on the people, but sometimes I’m invited places to kind of brighten up a dinner table like a musician who’ll play the piano after dinner, and I know you’re not really invited for yourself. You’re just an ornament.

When I was five I think, that’s when I started wanting to be an actress. I loved to play. I didn’t like the world around me because it was kind of grim, but I loved to play house. It was like you could make your own boundaries. It goes beyond house; you could make your own situations and you could pretend, and even if the other kids were a little slow on the imagining part, you could say, “Hey, what about if you were such and such, and I were such and such, wouldn’t that be fun?” And they’d say, “Oh, yes,” and then I’d say, “Well, that will be a horse and this will be …” It was play, playfulness. When I heard that this was acting, I said that’s what I want to be. You can play. But then you grow up and find out about playing, that they make playing very difficult for you. Some of my foster families used to send me to the movies to get me out of the house and there I’d sit all day and way into the night. Up in front, there with the screen so big, a little kid all alone, and I loved it. I loved anything that moved up there and I didn’t miss anything that happened and there was no popcorn either.

When I was 11, the whole world was closed to me. I just felt I was on the outside of the world. Suddenly, everything opened up. Even the girls paid a little attention to me because they thought, “Hmmm, she’s to be dealt with!” And I had this long walk to school, two and a half miles [there], two and a half miles back. It was just sheer pleasure. Every fellow honked his horn, you know, workers driving to work, waving, you know, and I’d wave back. The world became friendly. All the newspaper boys when they delivered the paper would come around to where I lived, and I used to hang from the limb of a tree, and I had sort of a sweatshirt on. I didn’t realise the value of a sweatshirt in those days, and then I was sort of beginning to catch on, but I didn’t quite get it, because I couldn’t really afford sweaters. But here they come with their bicycles, you know, and I’d get these free papers and the family liked that, and they’d all pull their bicycles up around the tree and then I’d be hanging, looking kind of like a monkey, I guess. I was a little shy to come down. I did get down to the curb, kinda kicking the curb and kicking the leaves and talking, but mostly listening. And sometimes the family used to worry because I used to laugh so loud and so gay; I guess they felt it was hysterical. It was just this sudden freedom because I would ask the boys, “Can I ride your bike now?” and they’d say, “Sure.” Then I’d go zooming, laughing in the wind, riding down the block, laughing, and they’d all stand around and wait till I came back. But I loved the wind. It caressed me. But it was kind of a double-edged thing. I did find, too, when the world opened up that people took a lot for granted, like not only could they be friendly, but they could suddenly get overly friendly and expect an awful lot for very little. When I was older, I used to go to Grauman’s Chinese Theatre and try to fit my foot in the prints in the cement there. And I’d say, “Oh, oh, my foot’s too big! I guess that’s out.” I did have a funny feeling later when I finally put my foot down into that wet cement. I sure knew what it really meant to me. Anything’s possible, almost.

It was the creative part that kept me going, trying to be an actress. I enjoy acting when you really hit it right. And I guess I’ve always had too much fantasy to be only a housewife. Well, also, I had to eat. I was never kept, to be blunt about it; I always kept myself. I have always had a pride in the fact that I was my own. And Los Angeles was my home, too, so when they said, “Go home!” I said, “I am home.” The time I sort of began to think I was famous, I was driving somebody to the airport, and as I came back there was this movie house and I saw my name in lights. I pulled the car up at a distance down the street; it was too much to take up close, you know, all of a sudden. And I said, “God, somebody’s made a mistake.” But there it was, in lights. And I sat there and said, “So that’s the way it looks,” and it was all very strange to me, and yet at the studio they had said, “Remember, you’re not a star.” Yet there it is up in lights. I really got the idea I must be a star or something from the newspapermen; I’m saying men, not the women who would interview me and they would be warm and friendly. By the way, that part of the press, you know, the men of the press, unless they have their own personal quirks against me, they were always very warm and friendly and they’d say, “You know, you’re the only star,” and I’d say, “Star?” and they’d look at me as if I were nuts. I think they, in their own kind of way, made me realise I was famous.

I remember when I got the part in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. Jane Russell – she was the brunette in it and I was the blonde. She got $200,000 for it, and I got my $500 a week, but that to me was, you know, considerable. She, by the way, was quite wonderful to me. The only thing was I couldn’t get a dressing room. Finally, I really got to this kind of level and I said, “Look, after all, I am the blonde, and it is Gentlemen Prefer Blondes!” Because still they always kept saying, “Remember, you’re not a star.” I said, “Well, whatever I am, I am the blonde!” And I want to say to the people, if I am a star, the people made me a star. No studio, no person, but the people did. There was a reaction that came to the studio, the fan mail, or when I went to a premiere, or the exhibitors wanted to meet me. I didn’t know why. When they all rushed toward me I looked behind me to see who was there and I said, “My heavens!” I was scared to death. I used to get the feeling, and sometimes I still get it, that sometimes I was fooling somebody; I don’t know who or what, maybe myself.

I’ve always felt toward the slightest scene, even if all I had to do in a scene was just to come in and say, “Hi,” that the people ought to get their money’s worth and that this is an obligation of mine, to give them the best you can get from me. I do have feelings some days when there are scenes with a lot of responsibility toward the meaning, and I’ll wish, “Gee, if only I had been a cleaning woman.” On the way to the studio I would see somebody cleaning and I’d say, “That’s what I’d like to be. That’s my ambition in life.” But I think that all actors go through this. We not only want to be good, we have to be. You know, when they talk about nervousness, my teacher, Lee Strasberg, when I said to him, “I don’t know what’s wrong with me but I’m a little nervous,” he said, “When you’re not, give up, because nervousness indicates sensitivity.” Also, a struggle with shyness is in every actor more than anyone can imagine. There is a censor inside us that says to what degree do we let go, like a child playing. I guess people think we just go out there, and you know, that’s all we do. Just do it. But it’s a real struggle. I’m one of the world’s most self-conscious people. I really have to struggle.

I’ve always felt toward the slightest scene, even if all I had to do in a scene was just to come in and say, “Hi,” that the people ought to get their money’s worth and that this is an obligation of mine, to give them the best you can get from me. I do have feelings some days when there are scenes with a lot of responsibility toward the meaning, and I’ll wish, “Gee, if only I had been a cleaning woman.” On the way to the studio I would see somebody cleaning and I’d say, “That’s what I’d like to be. That’s my ambition in life.” But I think that all actors go through this. We not only want to be good, we have to be. You know, when they talk about nervousness, my teacher, Lee Strasberg, when I said to him, “I don’t know what’s wrong with me but I’m a little nervous,” he said, “When you’re not, give up, because nervousness indicates sensitivity.” Also, a struggle with shyness is in every actor more than anyone can imagine. There is a censor inside us that says to what degree do we let go, like a child playing. I guess people think we just go out there, and you know, that’s all we do. Just do it. But it’s a real struggle. I’m one of the world’s most self-conscious people. I really have to struggle.

An actor is not a machine, no matter how much they want to say you are. Creativity has got to start with humanity and when you’re a human being, you feel, you suffer. You’re gay, you’re sick, you’re nervous or whatever. Like any creative human being, I would like a bit more control so that it would be a little easier for me when the director says, “One tear, right now,” that one tear would pop out. But once there came two tears because I thought, “How dare he?” Goethe said, “Talent is developed in privacy,” you know? And it’s really true. There is a need for aloneness, which I don’t think most people realise for an actor. It’s almost having certain kinds of secrets for yourself that you’ll let the whole world in on only for a moment, when you’re acting. But everybody is always tugging at you. They’d all like sort of a chunk of you.

I think that when you are famous every weakness is exaggerated. This industry should behave like a mother whose child has just run out in front of a car. But instead of clasping the child to them, they start punishing the child. Like you don’t dare get a cold. How dare you get a cold! I mean, the executives can get colds and stay home forever and phone it in, but how dare you, the actor, get a cold or a virus. You know, no one feels worse than the one who’s sick. I sometimes wish, gee, I wish they had to act a comedy with a temperature and a virus infection. I am not an actress who appears at a studio just for the purpose of discipline. This doesn’t have anything at all to do with art. I myself would like to become more disciplined within my work. But I’m there to give a performance and not to be disciplined by a studio! After all, I’m not in a military school. This is supposed to be an art form, not just a manufacturing establishment. The sensitivity that helps me to act, you see, also makes me react. An actor is supposed to be a sensitive instrument. Isaac Stern takes good care of his violin. What if everybody jumped on his violin?

You know a lot of people have, oh gee, real quirky problems that they wouldn’t dare have anyone know. But one of my problems happens to show: I’m late. I guess people think that why I’m late is some kind of arrogance and I think it is the opposite of arrogance. I also feel that I’m not in this big American rush, you know, you got to go and you got to go fast but for no good reason. The main thing is, I want to be prepared when I get there to give a good performance or whatever to the best of my ability. A lot of people can be there on time and do nothing, which I have seen them do, and you know, all sit around sort of chit chatting and talking trivia about their social life. Gable said about me, “When she’s there, she’s there. All of her is there! She’s there to work.”

You know a lot of people have, oh gee, real quirky problems that they wouldn’t dare have anyone know. But one of my problems happens to show: I’m late. I guess people think that why I’m late is some kind of arrogance and I think it is the opposite of arrogance. I also feel that I’m not in this big American rush, you know, you got to go and you got to go fast but for no good reason. The main thing is, I want to be prepared when I get there to give a good performance or whatever to the best of my ability. A lot of people can be there on time and do nothing, which I have seen them do, and you know, all sit around sort of chit chatting and talking trivia about their social life. Gable said about me, “When she’s there, she’s there. All of her is there! She’s there to work.”

I was honoured when they asked me to appear at the president’s birthday rally in Madison Square Garden. There was like a hush over the whole place when I came on to sing Happy Birthday, like if I had been wearing a slip, I would have thought it was showing or something. I thought, “Oh, my gosh, what if no sound comes out!”

A hush like that from the people warms me. It’s sort of like an embrace. Then you think, by God, I’ll sing this song if it’s the last thing I ever do, and for all the people. Because I remember when I turned to the microphone, I looked all the way up and back, and I thought, “That’s where I’d be, way up there under one of those rafters, close to the ceiling, after I paid my two dollars to come into the place.” Afterwards they had some sort of reception. I was with my former father-in-law, Isadore Miller, so I think I did something wrong when I met the president. Instead of saying, “How do you do?” I just said “This is my former father-in-law, Isadore Miller.” He came here an immigrant and I thought this would be one of the biggest things in his life. He’s about 75 or 80 years old and I thought this would be something that he would be telling his grandchildren about and all that. I should have said, “How do you do, Mr President,” but I had already done the singing, so well you know. I guess nobody noticed it.

Fame has a special burden, which I might as well state here and now. I don’t mind being burdened with being glamorous and sexual. But what goes with it can be a burden. I feel that beauty and femininity are ageless and can’t be contrived, and glamour, although the manufacturers won’t like this, cannot be manufactured. Not real glamour; it’s based on femininity. I think that sexuality is only attractive when it’s natural and spontaneous. This is where a lot of them miss the boat. And then something I’d just like to spout off on. We are all born sexual creatures, thank God, but it’s a pity so many people despise and crush this natural gift. Art, real art, comes from it, everything.

I never quite understood it, this sex symbol. I always thought symbols were those things you clash together! That’s the trouble, a sex symbol becomes a thing. I just hate to be a thing. But if I’m going to be a symbol of something I’d rather have it sex than some other things they’ve got symbols of! These girls who try to be me, I guess the studios put them up to it, or they get the ideas themselves. But gee, they haven’t got it. You can make a lot of gags about it like they haven’t got the foreground or else they haven’t the background. But I mean the middle, where you live.

All my stepchildren carried the burden of my fame. Sometimes they would read terrible things about me and I’d worry about whether it would hurt them. I would tell them: don’t hide these things from me. I’d rather you ask me these things straight out and I’ll answer all your questions.

I wanted them to know of life other than their own. I used to tell them, for instance, that I worked for five cents a month and I washed one hundred dishes, and my stepkids would say, “One hundred dishes!” and I said, “Not only that, I scraped and cleaned them before I washed them.” I washed them and rinsed them and put them in the draining place, but I said, “Thank God I didn’t have to dry them.”

I was never used to being happy, so that wasn’t something I ever took for granted. You see, I was brought up differently from the average American child because the average child is brought up expecting to be happy. That’s it: successful, happy, and on time. Yet because of fame I was able to meet and marry two of the nicest men I’d ever met up to that time.

I don’t think people will turn against me, at least not by themselves. I like people. The “public” scares me, but people I trust. Maybe they can be impressed by the press or when a studio starts sending out all kinds of stories. But I think when people go to see a movie, they judge for themselves. We human beings are strange creatures and still reserve the right to think for ourselves.

Once I was supposed to be finished, that was the end of me. When Mr Miller was on trial for contempt of congress, a certain corporation executive said either he named names and I got him to name names, or I was finished. I said, “I’m proud of my husband’s position and I stand behind him all the way,” and the court did too. “Finished,” they said. “You’ll never be heard of.”

It might be a kind of relief to be finished. You have to start all over again. But I believe you’re always as good as your potential. I now live in my work and in a few relationships with the few people I can really count on. Fame will go by, and, so long, I’ve had you fame. If it goes by, I’ve always known it was fickle. So at least it’s something I experienced, but that’s not where I live.

· Copyright 1962 Life Inc. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.